Table of Contents

Nikhil Rao, Implementing IPv6 support in gPXE

Quicklink: Timeline

About the project

My project is titled Implementing IPv6 support in gPXE. Here are some snippets from my proposal.

Synopsis

gPXE uses uIP to implement its TCP/IP stack. uIP is an implementation of the TCP/IP stack which uses a fraction of the resources used by a full fledged TCP/IP implementation.

The project is to implement support for IPv6. uIP (in its current avatar) tightly integrates the TCP and IP layers in order to save code size. As a result, it is not easy to replace IPv4 with any other network layer protocol in uIP. This project aims to re-design the TCP/IP stack of gPXE in order to facilitate IPv6 implementation.

Deliverables

The final deliverables for the project are:

- A clean, well-defined interface between the transport-layer and network-layer. The interface would be generic enough to allow any transport layer protocol to interact with any network layer protocol

- Re-design and implementation of the TCP/IP stack using the proposed interface (which fits within the gPXE API)

- Minimal support for IPv6

The stretch goals for the project are:

- Extension of the gPXE API to include UDP

- An implementation of UDP/IP (within the extended gPXE API)

- Support for additional features in IPv6

Plan of action

Main goals:

Investigate the working of uIPDefine bare necessary requirements of transport layer and network layerDefine the interface between these layers based on the requirements- Implement the TCP, IP modules using the interface

- Test implementation; Re-implement if necessary

- Increase requirements if necessary and go back to step 2

- Investigate minimum requirements to support IPv6

- Extend interface/requirements if necessary and go back to step 2

- Implement IPv6

- If time permits, implement stretch goals

Stretch goals:

- Investigate UDP implementation in Etherboot-5.4 and earlier

- Extend interface/requirements if necessary and perform steps 2 - 5

- Implement UDP support

- Investigate various features that can be added to IPv6

- Perform steps 7 - 8

Notes, ideas and concepts

I have tried to update my blog as frequently as possible with my thoughts. Here are some important notes which have been edited after IRC conversations, e-mails and IM sessions with Michael and Marty.

Implementing TCP

gPXE network infrastructure

Physical layer

Let us assume we are working with a RTL8139 driver. Further let us assume that we are using the Ethernet link layer protocol and the uIP stack to implement TCP/IP in gpxe. This short note will describe how data is received from the driver, queued and processed by gpxe's network stack.

I am not too sure about the architecture of the RTL8139 driver. According to my understanding (and a quick perusal of src/drivers/net/rtl8139.c), RTL8139 maintains a buffer for receiving packets. The structure of this buffer is:

struct rtl8139_rx {

void *ring;

unsigned int offset;

};

The RTL8139 NIC structure contains one such buffer for receiving packets and a similar buffer for transmitting packets:

struct rtl8139_nic {

struct threewire eeprom;

unsigned short ioaddr;

struct rtl8139_tx tx;

struct rtl8139_rx rx;

};

There are a bunch of functions to perform various tasks, such as opening the NIC, reading the MAC address, resetting the NIC, closing the NIC, etc. static void rtl_poll(struct net_device *netdev) is used to poll RTL8139 to check for received packets. This function takes a network device as an argument. The private data of the network device stores the rtl8139_nic structure. If data is available, it allocates a packet buffer of the appropriate size and copies the data from the driver into the packet buffer. It then calls void netdev_rx(struct net_device *netdev, struct pk_buff *pkb) passing the network device and packet buffer as arguments. The function netdev_rx() performs a very simple task. It fills up ll_protocol of the packet buffer with information from netdev and then adds the packet buffer to the rx_queue. The packet is picked up for processing by the link layer protocol (IPv4) when int net_rx_process() is called.

Link layer

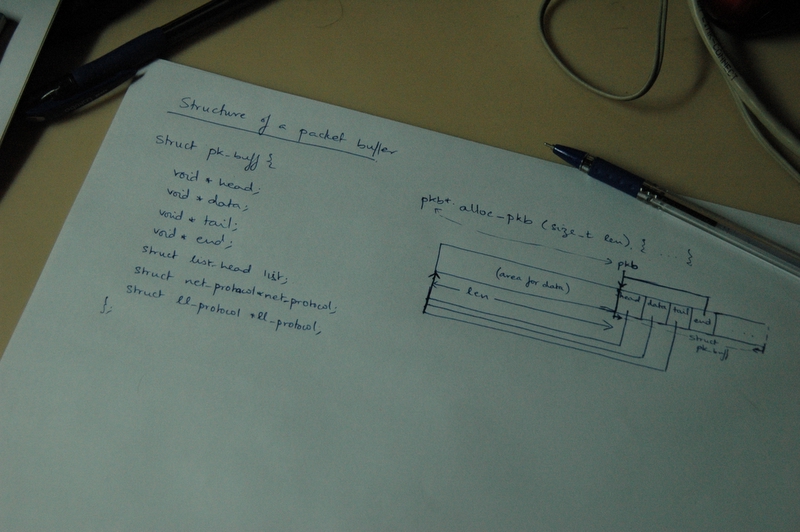

The packet buffer is an interesting concept detailed in src/include/gpxe/pkbuff.h and src/net/pkbuff.c. The structure used to represent a network packet within gpxe is:

struct pk_buff {

void *head;

void *data;

void *tail;

void *end;

struct list_head list;

struct net_protocol *net_protocol;

struct ll_protocol *ll_protocol;

};

The first four pointers are used to demarcate the buffer and data boudaries. The list structure maintains a list of all devices/entities this buffer is a member of (such as rx_queue, etc.). The net_protocol and ll_protocol pointers point to the network and link layer protocols respectively.

Now, the interesting part is in the buffer allocation function, struct pk_buff * alloc_pkb(size_t len), given in src/net/pkbuff.c. It takes the requested length of the buffer as an input argument. It is usually called from rtl_poll() while checking for received data. The packet buffer structure comes immediately after the data. The allocation can be represented abstractly as:

A bunch of functions are provided in src/include/gpxe/pkbuff.h and src/net/pkbuff.c for appending, prepending, etc. data.

A network device is represented using the following structure (src/include/gpxe/netdevice.h):

struct net_device {

int (* transmit) (struct net_device *netdev, struct pk_buff *pkb);

void (* poll) (struct net_device *netdev);

struct ll_protocol *ll_protocol;

uint8_t ll_addr[MAX_LL_ADDR_LEN];

void *priv;

};

Every network device has to implement two functions - transmit() and poll() which send data and poll for new data respectively. A network device is also associated with a link layer protocol (which it implements) and a link layer address. If the link layer protocol is Ethernet, then the link layer address it the MAC address of the network interface. The link layer protocol is represented as (src/include/gpxe/netdevice.h):

struct ll_protocol {

const char *name;

int (* route) (struct net_device *netdev, const struct net_header *nethdr, struct ll_header *llhdr);

void (* fill_llh) (const struct ll_header *llhdr, struct pk_buff *pkb);

void (* parse_llh) (const struct pk_buff *pkb, struct ll_header *llhdr);

const char* (*ntoa) (const void *ll_addr);

uint16_t ll_proto;

uint8_t ll_addr_len;

uint8_t ll_header_len;

};

Every link layer protocol has to implement route(), fill_llh(), parse_llh and ntoa(). The function route() performs link layer routing. It constructs a generic link layer header llhdr from a generic network layer header nethdr. The function fill_llh() is used to fill the media-specific link layer header. Similarly parse_llh() parses the link layer header in the packet buffer and fills in the generic link layer header llhdr. ntoa() is used to represent a link layer address in a human readable format.

The ethernet protocol implements these functions in src/net/ethernet.c as eth_route(), eth_fill_llh(), eth_parse_llh() and eth_ntoa() respectively.

Currently, uIP supports only a single instance of a network device. This single instance is called static_single_netdev within the code (refer src/net/netdev.c). The functions alloc_netdev() and register_netdev() should still be used to allocate and register a network device (although in the current implementation the code will be optimized out). There is a received packet queue, rx_queue, which maintains a list of received packet buffers. In the current setup, netdev→poll() is set to point to rtl_poll() when the RTL network device is probed in rtl_probe() (refer src/drivers/net/rtl8139.c).

A single step network operation is peformed by calling static void net_step(struct process *process). This function polls all the network devices for new packets using int net_poll(). This function polls for packets on all network devices by calling netdev→poll() and returns true if there are packets present in the receive queue (rx_queue in our case). net_step() handles at most one received packet at a time. It dequeues the received packet using struct pk_buff * net_rx_dequeue() and then processes the received packet using int net_rx_process(struct pk_buff *pkb). After this processing is complete, it schedules itself using the schedule() function.

The process function, int net_rx_process(struct pk_buff *pkb), processes a received packet at the link layer. Note that the link layer protocol is specified in the packet buffer in the field ll_protocol. This function fills up a generic link layer header llhdr by parsing the media specific components of the link layer header in the packet. The link layer header is represented as (refer src/include/gpxe/netdevice.h):

struct ll_header {

struct ll_protocol *ll_protocol;

int flags;

uint8_t dest_ll_addr[MAX_LL_ADDR_LEN];

uint8_t source_ll_addr[MAX_LL_ADDR_LEN];

uint16_t net_proto;

};

A generic link layer header consists of a pointer to the link layer protocol (in this case, to the ethernet link layer protocol), a field for flags (which is a bitwise OR of zero or more PKT_FL_XXX values, a destination and source link layer address (in the case of ethernet, a 48 bit address, where MAX_LL_ADDR_LEN = 6) and a 16 bit identification of the network protocol in the IP datagram.

The files src/include/gpxe/ethernet.h and src/net/ethernet.c contain the specifications for the ethernet protocol along with definitions for the various methods the protocol has to implement. The ethernet header is represented as (refer src/include/gpxe/if_ether.h):

struct ethhdr {

uint8_t h_dest[ETH_ALEN];

uint8_t h_source[ETH_ALEN];

uint16_t h_protocol;

};

The ethernet header is mapped on to the link layer header of the received packet and the corresponding fields are copied in to the generic link layer header llhdr. net_rx_process() then identifies the network layer protocol using the struct net_protocol * find_net_protocol(int net_proto) function and passing llhdr.net_proto as an argument to it. It sets the network protocol field net_protocol in the packet buffer to the protocol returned by the find_net_protocol(). It then strips off the link layer header and hands the packet buffer to the network layer (IP) to process by calling int net_protocol→rx_process(struct pk_buff *pkb).

Network layer

A network protocol is represented as (src/include/gpxe/netdevice.h):

struct net_protocol {

const char *name;

int (* route) (const struct pk_buff *pkb, struct net_header *nethdr);

int (* rx_process) (struct pk_buff *pkb);

const char* (*ntoa) (const void *net_addr);

uint16_t net_proto;

uint8_t net_addr_len;

};

Every network protocol has to implement the functions route(), rx_process() and ntoa(). The function route() performs network layer routing. It fills in the network header nethdr with enough information to allow the link layer to route the packet. The function rx_process() processes a received packet and ntoa() represents the network address in a human readable format.

The IPv4 protocol implements these functions in src/net/ipv4.c as ipv4_route(), ipv4_rx() and ipv4_ntoa() respectively.

In the current setup, the packet is handed over to uIP to process at this step. When net_protocol→rx_process() is called, the caller passes the packet buffer as an argument. The uIP stack is set up and the packet is copied into uip_buf as specified by uIP. The function uip_input() is then called and the packet is processed.

When uip_input() returns, it could have some data in uip_buf (which needs to be sent out). I will cover this in the next section on sending data.

uIP TCP/IP stack

The uIP module is defined in src/net/uip/uip.h, src/net/uip/uipopt.h, src/net/uip/uip_arch.h, src/net/uip/uip.c and src/net/uip/uip_arch.c. Internally, uip_input() calls the TCP/IP state machine (implemented in uip_process()) with UIP_DATA passed into it as an argument. This indicates that a packet has been received and needs to be processed.

The uip_process() function is split into two parts - one that handles periodic firings of uip_process() and another that handles input processing. The second part is invoked in this case. The IPv4 header is processed in the following steps:

- Check validity of IPv4 header. As uIP does not process options, it expects the header length to be of length 5 measured as 32 bit words.

- Check the size of the packet to ensure uip_len and the length specified in the IP header are the same.

- Check if the received packet is a fragmented packet. If so, then call uip_reass() which reassembles the fragments [and exit].

- Do some ICMP processing if we are configured to use ping IP address configuration and our IP address is 0.0.0.0

- Check if the packet is destined for our IP address. If not, then drop the packet.

- Compute and check the checksum of the IP header.

- Check the transport layer protocol and invoke the appropirate module.

Currently the uIP stack supports only TCP, UDP and ICMP.

ICMP processing

uIP is set up to handle only ICMP_ECHO (and, if configured, ICMP_PINGADDRCONF) processing. In ICMP_ECHO processing, the type of the ICMP message is changed to ICMP_ECHO_REPLY, the checksum is calculated and addresses are swapped. The ICMP packet is placed on the buffer. Note that the length of the buffer, uip_len, is not changed since the outgoing packet is the same size as the incoming packet. The function returns and this packet is sent (refer the next section on sending data).

Transport Layer

UDP processing

The UDP processing of uIP does not do anything to the UDP/IP headers. It sends the information back to the UDP application which does all the hard work. The UDP state machine checks the checksum of the UDP packet if it is configured to do so. It then proceeds to check which UDP connection the packet should go to. If it finds a connection, it strips the UDP header, sets the appropriate flags and sends it to the application via UIP_UDP_APPCALL().

If the application wants to send data it places the data in the app_data buffer and sets uip_slen to the length of the data. When uIP returns, it checks if uip_slen is non-zero which indicates that the application wants to send some data. It then proceeds to filling in the transport and network layer headers.

TCP processing

TCP processing proceeds in the following steps:

- Compute and check the TCP checksum

- Demux this TCP segment between the TCP connections; depending on the type of packet, process accordingly

- Check all active connections that are expecting a SYN,ACK packet after sending a SYN packet; if found, go to 4.

- Check if it is the SYN flag is set; if so, then it is an old duplicate - send a RST and exit.

- Check all listen connections to see if the destination ports match; if nothing is found send a RST and exit.

- If incoming packet is intended for a listening port (2.c)

- Search for a empty connection

- Fill in all necessary fields

- Change connection state to SYN_RCVD

- Check TCP MSS option if available and use it to set MSS

- Send SYN,ACK packet

- If incoming packer is intended for an active connection (2.a)

- Check TCP RST and reset connection if set

- Calculate the length of the data send to us

- Check if the SEQ_NUM of the incoming packet is what we are expecting next; if not, send an ACK with the correct numbers in it.

- Check if the incoming segment ACKs any outstanding data; if so, update SEQ_NUM, reset the length of the outstanding data, calculate RTT estimations and reset the timer

- Switch based on the TCP state of the connection:

- CASE SYN_RCVD:

- If connection state is ACKDATA, change TCP state to ESTABLISHED; if not, drop the packet.

- Change connection state to CONNECTED

- If there is any data in the packet, put it in the buffer and set the connection state to NEWDATA

- Call the application

- CASE SYN_SENT:

- if the SYN and ACK flags are set and the connection is in the ACKDATA state, proceed

- Parse the MSS option if present

- Set the TCP state to ESTABLISHED

- Set the connection state to CONNECTED | NEWDATA

- Call the application

- CASE ESTABLISHED:

- If the packet is a FIN and there is no outstanding data, then close the connection and inform application

- Check URG flag to process urgent data

- If uip_len > 0, we have new data; set the connection state to NEWDATA and update the SEQ_NUM we acknowledge

- If the application has stopped dataflow using uip_stop() do not accept any new data

- Set the MSS

- Call the application

- CASE LAST_ACK:

- If ACK is received, then close the connection and call the application

- CASE FIN_WAIT_1:

- …

- CASE FIN_WAIT_2:

- …

- CASE TIME_WAIT:

- CASE CLOSING:

Application layer

The application layer is invoked through the gPXE TCP API.

Todo: Add sending data

So, what's wrong?

The uIP TCP/IP stack, as mentioned in my proposal, is very tightly packed. The entire processing takes place in one function uip_process(). As mentioned earlier, this is split into two parts - one for processing new data and another to periodically check timeouts and see if data is to be sent. uip_process() heavily relies on goto statements and as a result, adding support for a new protocol is a difficult.

Internally, we use packet buffers to hold packets and information about it. When the uIP stack is invoked, data is transfered from the packet buffer into the uip_buffer (which is a statically allocated space for the data in uIP). This is inefficient usage of memory.

Notes about the interface

In addition to the net_header, net_protocol, ll_header and ll_protocol data structures, we would need to represent trans_protocol, tcp_header and udp_header. We can first discuss UDP, since it is the simpler of the two transport protocols. We can then extend our discussions to TCP.

We can use the following structures to represent a UDP header, TCP header and a transport protocol respectively:

struct udp_header {

uint16_t source_port; // source port number

uint16_t dest_port; // destination port number

uint16_t length; // length of the udp segment

uint16_t chksum; // UDP checksum

};

struct tcp_header { // without options

uint16_t source_port; // source port number

uint16_t dest_port; // destination port number

uint32_t seq_num; // sequence number

uint32_t ack_num; // acknowledgement number

uint8_t offset; // offset, the last four bits are 0000 (reserved)

uint8_t flags; // flags, the first two bits are 00 when ECN is not used

uint16_t window; // advertised window

uint16_t chksum; // TCP checksum

uint16_t urg_ptr; // urgent data pointer, not used in our stack

};

struct trans_protocol {

const char *name;

/*

* Process a received packet.

*

* This function processes the transport layer headers and sends the data to the application layer.

*/

int (* rx_process) (struct pk_buff *pkb);

/*

* Transmit a packet

*

* This function breaks up the data stream into packets, adds the transport header and sends the packet

*/

void (* transmit) (struct pk_buff *pkb);

/*

* Transport layer protocol number

*/

uint16_t trans_proto;

};

When the transport layer receives a packet, a function like xxx_demux() is called to determine which connection the packet is meant for. When UDP is used, the source and destination port information is sufficient to determine the connection. In the case of TCP, a connection is identified by the tuple (remote_ip_addr, remote_port, local_ip_addr, local_port).

The network layer strips off the network layer headers and passes the packet buffer to the transport layer via the rx_process() function.

trans_protocol->rx_process(pkb)

The rx_process() function processes the transport layer headers and passes the information to the application layer. The application's callback function xxx_operations::newdata() is invoked to send data to the application layer.

Receiving packets

(using UDP/IPv4/Ethernet)

Device layer processing

Receiving a packet is completed in a single time slice in which net_step() runs. net_step() calls net_poll() which polls the device for data. If data is available, it enqueues the data in rx_queue and sets the link layer protocol in the packet buffer to the protocol implemented in the network device. net_step() then checks if a packet is available to process and calls net_rx_process() to process the packet.

Link layer processing

net_rx_process() parses the link layer header in the received packet. It determines which network layer protocol to use and sets the network protocol pointer of the packet buffer to this protocol. It strips off the link layer header and sends the packet to the network layer using the rx_process() routine of the network layer protocol

net_protocol = find_net_protocol(llhdr.net_proto); ... net_protocol->rx_process(pkb)

Network layer processing

Currently ipv4_protocol.rx_process() points to ipv4_rx(), which copies the packet to uip_buf and invokes the uIP stack. We need to replace this function with one that processes the network layer headers and transmits the packet to the transport layer. Something that looks like this:

struct ipv4_hdr {

uint8_t verhdrlen;

uint8_t service;

uint16_t len;

uint16_t ident;

uint16_t frags_offset;

uint8_t ttl;

uint8_t protocol;

uint16_t chksum;

struct in_addr src;

struct in_addr dest;

};

static int ipv4_rx(struct pk_buff *pkb) {

struct ipv4_hdr *iphdr = pkb->data;

int rc;

// process IPv4 header

// compute and check the checksum

if(ipv4_hdr_chksum(pkb) != iphdr->chksum) {

net_drop_pkt(pkb, ECHKSUM);

}

// check the ip version, header len

if(iphdr->verhdrlen != 0x45) {

net_drop_pkt(pkb, EVERHLEN);

}

// check destination IP address

/* how do you check the interface's network address?

* can you carry it along with the packet buffer? Like:

* if(pkb->if_net_addr != iphdr->dest) {

* net_drop_pkt(pkb, EDESTADDR);

* }

// check if this packet is a fragment and needs to be reassembled

if(iphdr->frags_offset ... ) { // if this is a fragment, then this returns true

ipv4_reassemble(pkb);

return 0;

}

// check ttl

if(iphdr->ttl == 0) {

// send an ICMP error message back to the sender

icmp_send(pkb, ETTL); // ICMP should take care of sending the packet out

}

// Packet is OK. Send it to transport layer.

rc = trans_rx_send(pkb, iphdr->protocol, (iphdr->verhdrlen & 0x0f));

return rc;

}

int trans_rx_send(struct pk_buff *pkb, uint16_t trans_proto, int iphdr_len) {

struct trans_protocol *trans_protocol;

int rc;

// extract transport layer info from packet

trans_proto = iphdr->protocol;

trans_protocol = find_trans_protocol(trans_proto);

pkb->trans_protocol = trans_protocol;

// strip network header and send to the transport layer

pkb_pull(pkb, iphdrlen);

rc = trans_protocol->rx_process(pkb);

return rc;

}

There are bunch of functions which need to be implemented. ipv4_reassemble() for example, takes the fragment, reassembles the whole packet and then calls trans_rx_send() to send it to the transport layer.

Transport layer processing

Let us assume that UDP is the transport layer protocol specified in iphdr→protocol (=17), then trans_protocol→rx_process() points to udp_rx_process(). UDP processing is simple: calculate and verify the checksum, demux and get the connection, invoke the application's callback functions.

static int udp_rx_process(struct pk_buff *pkb) {

struct udp_header *udphdr;

/* We need to create the UDP pseudo-header in order to compute the checksum.

* This depends on the network layer protocol. We could store the pseudo-header

* in the packet buffer in the network layer and use it to compute the cheksum.

* // in trans_rx_send(pkb) - after find_trans_protocol()

* ...

* pkb->trans_protocol = trans_protocol;

* pkb->pshdr = (pkb->net_protocol)->pshdr(pkb, trans_proto);

* ...

*/

if(udp_calc_chksum(pkb) != udphdr->chksum) {

udp_drop_pkt(pkb, ECHKSUM);

}

// demux and get the udp connection

udp_connection *conn = udp_demux(pkb); // returns the udp connection

// strip off UDP header

pkb_pull(pkb, UDP_LEN); // UDP_LEN = 64 bits .. 8 bytes

// inform connection of new data using the callbacks in udp_ops

( (conn->udp_ops)->newdata(pkb->data, pkb_len(pkb)));

...

}

TCP would require a much more complicated trans_protocol→rx_process() function which would check the state of the TCP connection and proceed accordingly.

IP fragment reassembly

IPv4 and IPv6 both support fragmentation and reassembly of IP packets. But the manner in which they do it is very different. IPv4 has it as part of its regular header while IPv6 an extended header for fragmented packets.

gPXE should have a framework to support IP fragment reassembly, whichever IP protocol is used. The reass_buffer structure can be used to handle the reassembly.

struct reass_buffer {

uint16_t ident; // identification number

uint8_t net_addr[MAX_NET_ADDR_LEN]; // datagram source address

net_protocol *net_protocol; // network layer protocol

struct pk_buff *reass_pkb; // the reassembled packet

[one of these two:

struct bitmap *bitmap; // bitmap to check if all the fragments have been received

list_head frag_headers; // list of fragment headers to do above task

]

uint8_t flags; // flags - bitwise OR of zero so more IP_REASS_XXX values

struct retry_timer reass_timer; // reassembly timer

};

We can create an instance of the reass_buffer structure every time a new fragment series is started. This way, I think multiple reassembly processes can be handled at any given time. We also need to maintain a list of all reassembly buffers.

We can collect fragments of the same fragment series using the identification number and the source network address to determine which fragment series the fragment belong to. Every time a new fragment arrives, its (ident, source_addr) is compared with the reass buffer's (ident, source_addr) and if it matches the contents are merged into reass_pkb.

reass_pkb is a packet buffer in which the actual reassembly takes place. The goal is that after the reassembly process, reass_pkb should be identical to the hypothetical packet buffer we would have received had fragmentation not occurred. I am still a little hazy about the details but I guess this is how I would proceed. On receiving the first fragment - i.e. when a new reass_buffer is created, the reass_pkb packet buffer will be allocated a factor times its length (from sources like this, we can put this factor = 2 or 3). If it is the last fragment in the fragment series, then we know exactly how much space needs to be allocated (offset + total length).

As new fragments come, the data is merged into this packet buffer (reass_pkb). We might need to do some juggling around with the size of the packet buffer - reallocate, shift data, etc. - which might be a little messy. Any suggestion to make this part clean is welcome :) and greatly appreciated :) I guess the moment we receive the last fragment the total size of the packet can be determined and all is well.

We would also need to remember whether the first fragment has been received, the last fragment has been received and if the reassembly has been completed. We can use the flags field to keep all this information.

IP_FRAG_FST 0x01 IP_FRAG_LST 0x02 IP_FRAG_FIN 0x04

The flags field is a bit wise OR or of zero or more of these values. The IP_REASS_LST flag is set when the received fragment does not have the frag bit set in its IP header (in the case of IPv4). IP_REASS_FST is set when the IP fragment is the first in the sequence, i.e. when the offset field of the IP header (again, IPv4) is 0. Setting the IP_REASS_FIN flag is a little more complex.

In order to determine whether or not we have received all fragments, we could use either one of the following two approaches. I prefer the first one since it is more space efficient.

We can maintain a list of the (offset, total-length) values of the fragments received. When the first fragment of a fragment series is received, we initialize this list using the info in this fragment's header. As more fragments are received, we add more elements to the list depending on the position of the fragment, i.e. a new element k is placed between elements i and j in the link list such that

offset_i >= offset_k >= offset_j offset_i + total-length_i <= offset_k offset_k + total-length_k <= offset_j

The flag IP_FRAG_FIN is set when,

- the

IP_FRAG_FSTflag has been set - the

IP_FRAG_LSTflag has been set - for every element i in the list (followed by element j), the following holds:

offset_i + total-length_i = offset_j

The other approach uses a bitmap. Fragment offsets are calculated in units of 8 octets. Let the total reassembled packet length be L, then we can create a bitmap of length L/8 bits such that each bit corresponds to one byte of the packet. As fragments are received and merged into reass_pkb, the corresponding bits in the bitmap are set to 1. When all bits are 1, IP_FRAG_FIN is set and the packet buffer is sent to the higher level protocol for processing.

Another aspect is the reassembly timer. When a reass_buffer is created, the reassembly timer is created and set to the MAX_FRAG_TIME value which is the maximum time in which the reassembly should occur. If the timer expires before the IP_FRAG_FIN flag is raised, we assume that one or more fragments are lost and the reassembly buffer is discarded. IMO the reassembly timer should be decremented in the time slice alloted to the network layer, i.e. in net_step().

When the IP_FRAG_FIN flag is set, the packet is sent to the transport layer protocol for processing. The reass_buffer is discarded and memory is released.

More on IP fragment reassembly

Last night, Michael and I had a long IM session in which we discussed the reassembly requirements. Here are the main points:

- We assume that the fragments are received in order. We do not need to remember where in the original packet the recived fragment fits. This greatly simplifies the process of reassembling fragments.

- If a fragment is received out of order, we simply assume that the missing fragment (before it) is lost and we discard the reassembly buffer.

- If the offset field of a fragment is equal to 0, then we create a new reassembly buffer for the fragment series as described in the earlier note.

- If the offset field if not set, we identify the fragment series. If the offset + total_length of the last received fragment in the fragment series is equal to the offset of the received fragment, we add the fragment to the fragment series. Else we discard the fragment series.

- If the more fragments field is not set, i.e. this is the last fragment of the series, on successfully adding the fragment, we invoke the transport layer's

rx_proces()function and pass the reassembled buffer into it. - We need to write

realloc_pkb()which will take a packet buffer and a new length, allocate a new packet buffer for the new length, copy the contents of the old packet buffer into the new one, and then free up the old packet buffer. This function will be useful in maintaining the reassembled buffer.

(I apologise for the verbose and hasty notes. I will compile a more elaborate one with code snippets soon)

To do list

- Document revised TX and RX paths through the network stack1).

- Figure out a way to pass generic information between layers

- Complete the UDP implementation

- Complete the IPv4 implementation

- Debug/test the UDP/IPv4 stack

- Implement fragment reassembly

Some fun stuff

Some of these pages are loaded with pictures and might get a little heavy to load on the main page. Hence the redirection. Sorry for the inconvenience.

About me

I am an computer science engineer from the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay (technically speaking, not yet an engineer since I haven't received my degree as yet). I am a photographer (yes, really!). And a drummer (sorry, no online songs… yet). I'm going to the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor to pursue my graduate studies in computer science.